| Home |

| Taking Responsibility |

| Global Warming |

| Local Food |

| Grow Your Own |

| About Start Now and Glenn & Jean |

| Contact Us |

|

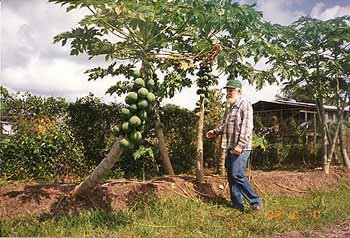

The Belize Project In 1980, the Start Now impresarios (Glenn and Jean, see About Us) bought quite a lot of land in Belize, Central America. The land was deemed worthless, and therefore was cheap. Belize, the former British Honduras, was pillaged for mahogany for sailing ships in the colonial days. As we now know, clear cut tropical forests don't regenerate, because almost all of the organic material necessary to support life is in the trees. Take them away, and the land that is left is devoid of topsoil and exposed to the deluge of tropical rain, about 130 inches per year in the area where we bought land. The rain quickly washes away the remaining fertility, and the land remains barren. You might believe, as we did, that the soil, after all, is only necessary for plants to stand in, and that the addition of purchased fertilizer will correct the barrenness problem. This is what the "green revolution" taught in decades past. Soluble chemical fertilizer acts quickly, and plants respond with rapid growth. We planned citrus orchards for the empty land. We thought that they would increase the value of the land and make our fortune. The time was right for new citrus orchards. Massive plantings in Brazil had been killed by rampant disease. We raised trees on a disease resistant rootstock, expecting to fill a hungry market. Poor drainage kept our land too soggy for much of the year, but some earth moving fixed that problem. We laid out several hundred acres of new orchards, and created Parrot Hill Farm. We shipped in and applied fertilizer, and sure enough, the trees put on a spurt of growth. It wasn't long at all, however, before growth slowed, leaves looked pale, and nutrient deficiencies appeared. We applied more fertilizer. The cycle repeated, a bit shorter this time. Soon we realized that the soluble fertilizer was washing away in the heavy rains, and the barren, sandy soil itself had nothing to offer. We couldn't buy enough fertilizer to keep the trees going, and certain failure was looming. We didn't give up, but looked for better answers. We found them in books of soil science and organic agriculture. This led us to the discovery of much wider problems resulting from the use of agricultural chemicals, problems with worldwide significance, including global warming, which is only now coming to widespread acceptance as a dominant issue. Our research back then in the eighties led us to organic agriculture solutions, which brought about dramatic recovery of our orchards, and more than that, resulted in creation of deep and fertile topsoil where there was once only worthless sand. (For more information on the Parrot Hill Farm project, see "Agribusiness in the Tropics.") We thought the ecological significance of our project was more important than the fortune, and so invested the entire project into a newly formed non-profit corporation, Start Now, formed for the purpose of establishing and carrying on commercial projects which would improve earth's ecology. Parrot Hill Farm went on to diversify its orchards, develop techniques of large-scale composting from organic waste from the citrus, sugar and fish processing industries, construct raised beds to create fertile soil and facilitate vegetable production, and demonstrate water hyacinth sewage treatment methods. Parrot Hill Farm also became an educational training center for teaching these techniques. |

|

|||||||||||

The Wisconsin ProjectAfter thirteen years developing Parrot Hill Farm, we were ready for a change, and undertook a new project in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, applying what we had learned in Belize in a different climate and with different problems. In 1993,we bought a small piece of land near Eau Claire, Wisconsin, 57 acres, which had been used for conventional farming for many years, a relentless cycle of corn and soybeans, using chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The chemicals killed soil microorganisms. The exposed soil during the corn cycle eroded away. Tractor traffic through the fields compacted the ground. The result was lifeless, sandy soil with virtually no topsoil or natural fertility, very similar to the unimproved land we started with in Belize. We undertook a recovery program, using the knowledge we acquired down South. We halted all applications of chemicals, added rock dust to the fields to restore depleted minerals, and planted a variety of grasses and legumes to let the healing process begin. With far less rain and a hard winter instead of a year round growing season, the process of recovery was much slower than in Belize, but our actions halted the soil degradation process, and improvement was apparent even in the first year. Instead of orchards, we planned organic vegetable production for the Eau Claire farm. To get a quick start, we imported fertility in the form of many tons of composted turkey manure. To extend the growing season, we built covered growing houses for intensive planting, and built raised beds in them, which we filled with compost. We built a large solar greenhouse, 40 by 60 feet, in which to start our vegetable seedlings. We used straw bale construction for the greenhouse, erecting the first straw bale building in the state. And so, Start Now Gardens began. We sold vegetables in the Eau Claire farmers market, but soon developed the concept of community supported agriculture through a restaurant. The goal in local food production is to shorten the distance traveled between field and table. A difficulty in achieving this goal often arises in the cooking phase, since many busy people no longer cook very often, and find themselves buying foods in the grocery store which were grown and prepared in distant locations, the antithesis of local food. We set up a restaurant in Eau Claire called it Beautiful Soup, grew vegetables for the restaurant, and opened for business. The vegetables went from farm to kitchen to consumer. Start Now Gardens and Beautiful Soup were the Start Now projects of the nineties. |

|